Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There!

I’m anxious, neurotic, and methodical to a fault. I perseverate over minutiae and struggle to be flexible (yoga notwithstanding). Ubiquitous truisms like, “Relax, it’s just wine,” and, “Don’t worry. You can fix it later,” make me insane. The worst, I mean the worst, is “Just give it some time.” I toss and turn in bed, obsessing whether my yeast are dividing quickly enough. Maybe I should sneak into the winery at 3 am and warm up my bins, punch them down, or turn on some Marvin Gaye? Why can’t I do it now? 3 am is as good a time as any. It’s exhausting being the Center of the Universe. And even when I know what’s happening, I can’t overcome a compulsive instinct to muck around and triple-check one last time. This year, my zin crew harvested at night. The fruit came in cold, numbing my hands as I sorted through the freezing clusters. 24 hours later, after a night in the cold room, my berries measured 56°F. This was a big change from 2011, where my fruit was picked in mid-day heat, sitting at a balmy 77.5°F. And in 2011, my zin fermented a flash. Now it would make sense that cold berries initiate fermentation more slowly whereas warm ones ignite quickly. In fact, this is a well-known variation of the fermentation pattern known as “long lag.” Yeast don’t like the cold too much, so they’re sluggish and torpid when the juice is below 60°F. Even if you acclimate your yeast to the cold juice before pitching them into the bin, they won’t get it on right away. Body heat takes time.

This year, I knew I was facing a long lag. The day I inoculated, the juice was down at 54 or 55°F. The next day I texted a winemaking pal to say, “Hey, I hope I didn’t kill my yeast. I just think it’s a long lag.” Post inoculation day #3, I sat around mulling “the long lag.” I dug out a journal article to remind myself “slow fermentation initiation generally reflects…specific fermentation conditions (such as low juice or must temperature)” (Bisson 2000). I paced the winery. I drove myself nuts and finally called a courier to pick up a juice sample to scan under the microscope. What if I didn’t have any viable yeast? What if they were dying due to some unknown, undocumented factor the likes of which have never been faced by anyone in the history of wine making? Hello. Movies like Outbreak and Contagion are based on some whiff of scientific rigor. And when the courier showed up, I insisted on following him to the lab and looking under the scope myself, because I’m not pushy.

By the time we’d caravanned to the lab, my juice sample was visibly fizzy. He opened the test tube and an audible whoosh of CO2 preceded the volcanic eruption of sticky, purple juice. He looked askance. Luckily the pattern on his shirt camouflaged stains; I wanted to curl up into a ball and die. “Guess fermentation must’ve started in the car,” I muttered lamely.

The microbiologist was kind enough to e mail me photomicrographs of my yeast. At that point, he’d do anything to get me to leave. They’re “Glamour Shots,” a pal glibly joked. Next year I’ll be better prepared. My yeast will wear Prada.

The blue guys are dead, and all the other critters are very much alive. You can even see some budding and dividing. If anyone has any good tips for removing grape juice stains, please pass them along. In the interim, I’ve to some dry cleaning bills to cover.

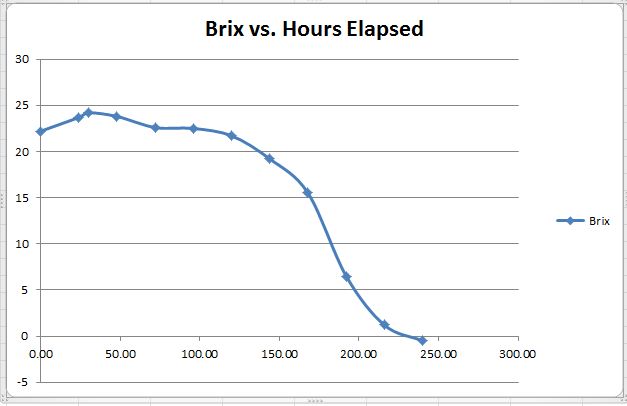

Below you can see the long lag before fermentation kicked in on the zin.