The Economics of the 2021 Wine Vintage - One Winemaker’s Perspective

The January 18, 2023 headline in the SF Chronicle notes that, “According to Silicon Valley Bank’s State of the U.S. Wine Industry Report, released on Wednesday, 71% of West Coast wineries said they intend to increase their bottle prices in 2023. Within Napa Valley specifically, 71% of owners also said they are planning an increase” (Esther Mobley 1/18/23 SF Chronicle). In the SVB report itself, authors note that “2022 bottle pricing dynamics is expected to continue into 2023, with 47 percent of survey respondents noting they will make small bottle-price increases in 2023.” And even with a “small” bottle price increase, small family wineries (like mine) are battling eroding margins and eating some costs ourselves. Why is this happening? Obviously, inflation is a factor. Consumers read about inflation, interest rates, and The Fed near daily in the newspaper. Certainly, the wine industry is not immune from the same economic pressures as other businesses or commodities. But the complex interconnection between wine growing and wine production, between the ag and the alcohol, offers innumerable permutations that affect the cost of the wine in your glass.

I am not an economist; I can’t use Excel properly; Brian is my CF(n)O. But from a winegrowing and winemaking perspective, let me share some insights based on the 2021 growing season, the vintage soon to be decorating retail shelves.

Let’s backtrack to 2020. Many wineries (mine included) grappled with smoke impact, and I didn’t vinify many of my typical vineyards. In other words, I opted out of harvesting particular vineyards and didn’t make much wine that year. Much at all. Like 60% less. And when you’re a wee winery (like mine), and you’ve got no economy of scale, making less will cost more. For me, producing less volume at the same cost of goods erodes margins. For example, whether I am paying to truck 5 pallets of glass or 25 pallets of glass to the winery, fuel surcharges and hourly trucking rates are fixed. So, in 2020, making less wine, costs more. There’s some context: after 2020, small wineries are already behind. That sets the stage for 2021. I think the vagaries of the 2021 growing season impacted wine economics pretty profoundly. Since winemaking starts in the vineyard, let’s consider the ’21 growing season.

The Growing Season Matters

2021 was a tough season in the vineyards. Up here in Sonoma, the 2020-2021 growing season proved to be the driest recorded since 1895, for both California more broadly and the North Coast, up where my vineyards live. Sonoma is typically reliant on winter rains to restore soil moisture and feed the vines until spring, when we typically begin irrigation. Not so in 2021. Without winter rain, growers were forced to irrigate earlier than anticipated. And even with winter irrigation (which is unusual up here), vine growth varied wildly.

Uneven is Inefficient

Dry soil resulted in uneven bud break which resulted in uneven shoot growth which resulted in uneven bloom, uneven fruit set, and uneven ripening. Uneven budbreak in March snowballs throughout the growing season, so that when you’re preparing to harvest wine grapes, some clusters are ripe, and others are not. This is not ideal. To remedy the variation requires lots of extra work in the vineyard, work that begins long before the fruit is ready to harvest. For example, extra shoots without fruit (called laterals) are plucked away to expose fruit to sunlight. If some laterals are tall and others are short, the efficiency of vineyard work suffers. Machine trimming requires multiple passes through the same rows, since the uneven shoots are at different heights and at different spacing. Obviously, the same work by hand is also slower to complete. And maybe growers want to retain certain specific laterals, on certain vines, where extra shade might be fortuitous during summer. These choices require time and expertise.

Uneven ripening is especially frustrating monitoring development after versaison. Growers discard clusters that fail to turn purple, juicy, and sweet. It’s called a “green drop,” when underripe clusters are removed from the vine. This ensures quality fruit with even sugar concentration, acid, and phenolic ripeness at harvest. As you can guess, a green drop also requires growers to traipse through every row and examine every cluster to cut away the lagging, green clusters. This takes time. And expertise. And additional passes in the vineyard, since one cluster is ahead of its neighbors while another is behind. In 2021, fruit was “touched” more times during the growing season than in years past. This is good for quality, even exceptional. That said, in 2021, same seasonal vineyard interventions required more passes through the same vines and more labor to complete the same work.

Small Crop Issues

Drought conditions exacerbated soil nutrient deficiencies and resulted in a smaller crop. Even if growers amend the soil, vines cannot uptake and use the micronutrients without water. In 2021, we saw fewer clusters on the vines, and the clusters were smaller. In wineag speak, this means cluster counts and cluster weights were down. Picking smaller clusters takes the same amount of time as bigger ones, so during harvest 2021, we spent the same number of hours picking fruit but with less yield. Again, I am not a finance person, but this is problematic.

From Grape to Bottle and Beyond

Homing in on the growing condition specific to the 2021 vintage offers some insight into the rising cost of premium wine grapes. And frankly, value brands are affected too. Machine trimmers and harvesters struggle with variation in the vineyard. Settings are readjusted; multiple passes are required. OK, so obviously wine production is inextricably tied to ag and wine growing conditions. But now you can appreciate some behind-the-scenes details. Mother Nature was especially punishing in 2021.

This sets up a perfect storm for 2021 wines. Pressure in the vineyard is compounded by the usual suspects: higher glass costs, higher transport costs, higher bottling costs, higher labor costs, more expensive printing and labels, paper shortages etc. And I imagine it is for these myriad reasons that wineries large and small are considering and enacting price increases. Again, let me reiterate: I am not an economist or a finance whiz or an accountant. I am just sharing with you my perceptions and my experience, as a winegrower and winemaker of small scale.

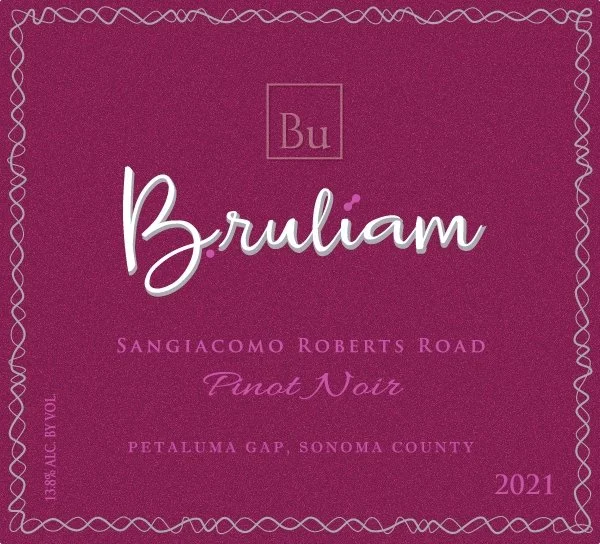

I am sorry this post sounds despondent. 2021 is a great vintage! The grapes had so much TLC in the vineyard, and great wines start with great grapes. Furthermore, drought conditions made for lower pest pressure - also good. Prepare to see terrific wines on the shelves, coming soon to your favorite retailer. Very soon. Many wineries (Bruliam included) are expediting their 2021’s to market to compensate for limited 2020 production. Know these wines will be great!!! But right now they are young. The 2021’s will need some time to blossom and develop. If you need something to drink now, look for 2018’s. Now 2018 was a slam dunk, near perfect growing season. We can thank Mother Nature for that one!!